IN JAPAN’S freezing north, Kuniko and Kazutaka Kon trudged through deep snow and howling winds to attend a rally for a new party that aims to derail Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s early election gamble.

About 250 mostly silver-haired voters crammed inside the auditorium of a community center in Akita, near the northern tip of Japan’s main island, to hear the plans and policies of the Centrist Reform Alliance.

The Kons say they’ve been unsettled by Takaichi’s remarks that Japan could deploy its military if China tried to seize Taiwan. The couple fear the premier is taking Japan too far to the right.

“We have to deliver a big ‘no’ to the Takaichi administration,” Kazutaka Kon, 79, said.

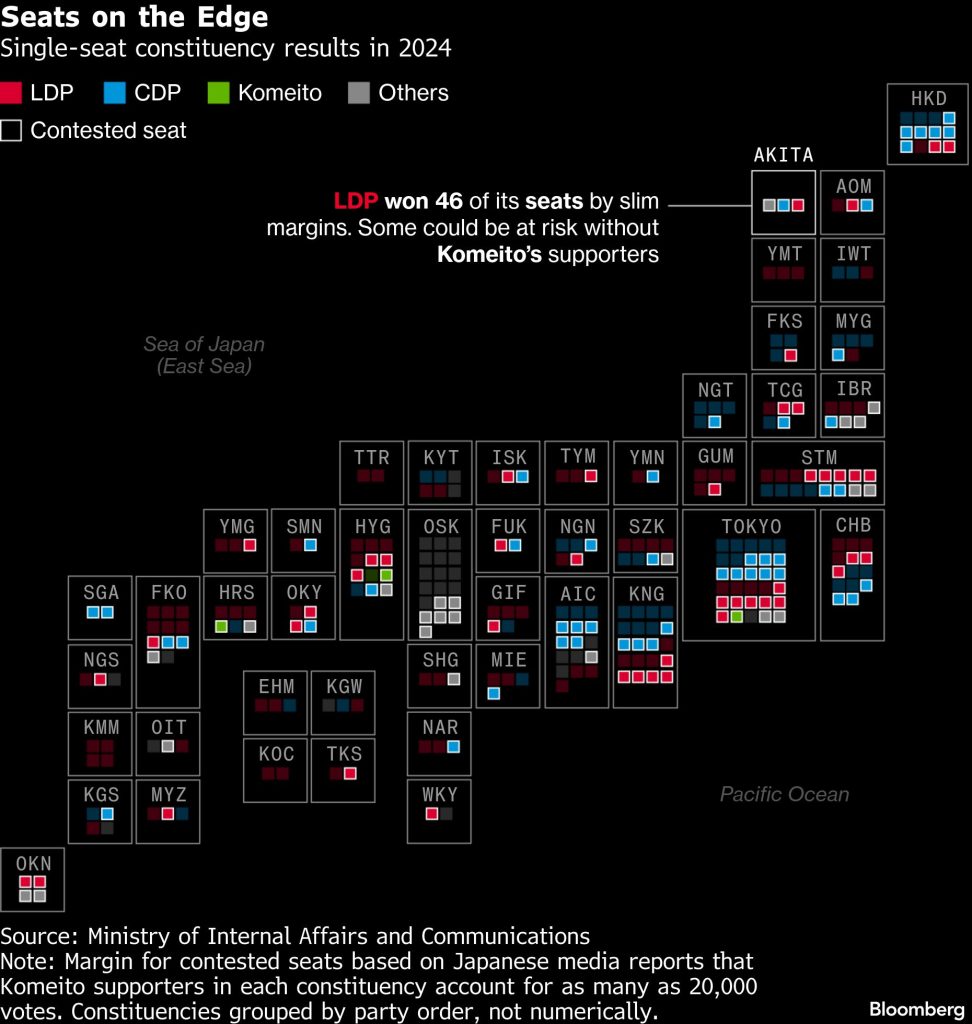

There are millions like the Kons across the nation whose votes could prove decisive in Japan’s 46 most tightly-contested seats. Those results will shape whether Takaichi secures a commanding win, barely scrapes through, or — an outcome the CRA has hoped for — loses control of the lower house. The nation’s verdict will also have major implications for markets.

Just three months into the job, Takaichi is banking on her strong approval ratings, more assertive stance on defense and promises of a sales tax cut and higher spending to add to the ruling coalition’s 233 seats in the 465-member House of Representatives, the parliament’s lower and more powerful chamber. She has indicated she will step down if that majority fails to grow, an outcome that would draw comparisons with the brief tenure of former UK Prime Minister Liz Truss.

Opinion polls suggest Takaichi’s Liberal Democratic Party will win comfortably, but the loss of a key election ally and the formation of the CRA less than a month ago are injecting uncertainty into the result.

The Kons are longtime supporters of Komeito, a party established to clean up Japanese politics and offer support to the needy with the backing of Buddhist organization Soka Gakkai. For the past quarter century, Komeito has repeatedly helped the LDP win elections through a mutual back-scratching deal tailored to Japan’s dual voting system.

People like the Kons would vote for the LDP candidate in their local constituency, knowing that in return, LDP voters would back their Komeito candidate in the corresponding proportional representation vote. The Kons voted for the LDP even after news emerged in 2023 that some of the party’s lawmakers had siphoned off undeclared fund-raising money.

“The money scandal was the worst,” said Kuniko Kon, 75. “I wish those lawmakers would just step down. I hated that people saw Komeito in the same way.”

That voting arrangement has now been turned on its head after Komeito bolted from the ruling party coalition in October. Komeito then merged with the largest opposition party, the Constitutional Democratic Party, in January, to form CRA. The new arrangement essentially means former CDP members will run in the constituencies as CRA candidates, while former Komeito members will run as CRA candidates in the PR vote.

The upper range of local media reports puts the average size of Komeito supporters in constituencies around the nation at around 20,000, a figure that is larger than the LDP’s winning margins in those 46 vulnerable seats.

The Kons will vote in Akita Constituency No. 1 where the LDP’s Hiroyuki Togashi won by just 872 votes in 2024. For the CRA, capturing Akita No. 1 would be a critical victory that demonstrates its ability to leverage Komeito support and expand its footprint as it tries to slow Takaichi’s rightward push.

Akita is known for its winter snow, hot springs and its delicious sake made from rice harvested in the region. But its scenic vistas belie its severe demographic crisis, with farmers aging and a lack of major economic opportunities sending young people to the big cities like Tokyo. Akita ranks the near bottom in national household incomes, making the pain of inflation acute.

Residents here also feel their peace threatened every time North Korea fires missiles toward the Sea of Japan. Before the winter, their sense of insecurity was fueled by a spate of attacks by marauding bears.

On stage at the community center, CRA candidate Shusaku Hayakawa, a 49-year-old Akita native, said he would revive the local economy by drawing on his past experience as a secretary to former Prime Minister Tsutomu Hata and as an entrepreneur.

“Akita is No. 1 on a list of disappearing cities — isn’t that sad? Shouldn’t we try to stop that?” Hayakawa said. “Politics isn’t necessary for strong regions or the powerful. Politics is necessary for the weak and the vulnerable.”

While the CRA looks to build momentum in Akita, Takaichi is also making progress in pulling back voters who strayed from the LDP at the last two elections with her more assertive policy stance.

Among LDP voters who have doubted the party is 55-year-old Shinichi Okamoto. Before Takaichi took the helm, Okamoto felt the LDP was drifting away from the conservative values embodied by the late Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, whose 2022 state funeral he attended in Tokyo. That’s why he left his ballot blank in the last election.

“It’s really important for the nation’s leader to lift up the people. And that’s exactly what Takaichi has done so well,” he said, after braving freezing snow and gusting winds to attend a rally for the LDP incumbent Togashi. “Some people say multiparty politics is better, but I believe we need a strong leader.”

Complicating the battle in Akita, and across the nation, is the emergence of a host of smaller parties with well-honed agendas that zoom in more closely on voter concerns about take-home pay, the cost of living and the growing presence of foreigners in the nation.

Opinion surveys show that the nationalist Sanseito and the center-right Democratic Party for the People will likely solidify their presence in parliament, further complicating the election picture.

Last week, as hail turned to snow, Sanseito candidate Miwako Sato delivered an outdoor speech near Akita Station.

“They say we need immigrants to compensate for labor shortages caused by the declining birthrate. That’s utter nonsense. They just want cheap labor,” Sato said via megaphones placed atop an election van. “If things continue like this, Japan will cease to be Japan.”

Some drivers waved their support as they passed. Sato won 13% of the vote — about 60,000 ballots — in last year’s upper-house election in a different voting district, contributing to an LDP candidate’s loss, an indication of Sanseito’s ability to shake up election results. The party won the second-largest number of votes in last year’s election, but that doesn’t always equate to victories in first-past-the-post seats.

“It really comes down to Japanese First,” said Hidetsugu Mogami, who listened closely to Sato, standing on an icy sidewalk. “We should prioritize Japanese people more. Let’s spend money on Japanese people.”

Still, Mogami said he was torn between voting for Sanseito and the DPP. “The LDP is not an option,” he said.

Minutes later, DPP candidate Sachiko Kimura spoke at the same spot, joined by party heavyweight Motohisa Furukawa.

Kimura, 39, was born and raised in Akita before becoming a lawyer and then a local lawmaker in the capital. A mother of two, she said she was returning to give something back to her hometown.

“The DPP has many young members, parents raising children, and female lawmakers,” she said. “Policies to raise take-home pay for working families and employees are moving forward. Let’s make progress here in Akita, too.”

For many in Akita, the LDP has drifted away from its core supporters and its conservative values for too long. A move by former LDP Agriculture Minister Shinjiro Koizumi to lower soaring rice prices last year appeared to focus on easing inflation pain in the cities, while ignoring the spiraling costs of farmers in the provinces.

That inflationary squeeze on small firms here continues to drive dissatisfaction.

Business has slowed since the year-end holidays at a seafood stall run by Hitoshi Kawamura and his father in Akita Citizens’ Market near the station.

“My fish aren’t selling, but the prices I pay keep going up,” Kawamura said as he sliced up cod. “After decades of LDP rule, if this is where we are, maybe it’s better they’re not in power.”

He favors eliminating the sales tax on food for good, as proposed by the CRA. But even though he attended the same school as the CRA candidate, he said he didn’t know much about the new alliance.

While for some voters Koizumi is the poster child for where the LDP has gone wrong, others take a different view. About 800 people squeezed into a 500-seat auditorium as Koizumi, now the nation’s defense minister, took the stage amid a throng of raised smartphones. The son of a legendary former prime minister, Koizumi lent his support to Togashi, an indication of how much importance the LDP is placing on shoring up seats that Komeito helped them win previously.

“What we need is someone who keeps their feet on the ground,” Koizumi said.

The overriding message of Togashi was to avoid complacency following the recent opinion polls. Predicted heavy snowfall in Japan’s first winter election in 36 years could be another wildcard.

Poor weather would normally be seen helping the bigger parties with organized voting support. But with opinion polls pointing to an LDP victory, more snow may end up boosting the chances of smaller parties as more ardent voters cast their ballots while ruling-party supporters stay at home, assuming that victory is already in the bag.

“You won’t know the outcome of this election until the very last moment, until the final tally is revealed,” Togashi told supporters. “I am consciously and desperately asking for your help.” –BLOOMBERG

The post Takaichi needs votes from a party that’s shunned her to win big appeared first on The Malaysian Reserve.