Auto Added by WPeMatico

It’s a dangerous, but lucrative business

by MUMBI GITAU & BAUDELAIRE MIEU

AT THE town of Gbapleu, a rope tied between two metal barrels separates Ivory Coast from Guinea. A thin trickle of traffic passes through the border post, mostly motorbikes or cars stuffed with passengers and overburdened with food and household items tied to their roofs.

For those who want to avoid the scrutiny of officials, there are other routes. Scattered throughout the region are dirt tracks that snake through the forests and grassland. After dark, motorcycle couriers arrive at warehouses in Ivorian towns near the frontier and load up with two or three sacks of cocoa, each weighing about 65kg. From around 10pm, the riders set out for the border in a convoy, dodging the checkpoints to carry beans into Guinea.

It’s a dangerous, but lucrative business. If they’re caught, smugglers face up to 10 years imprisonment or a fine of 50 million CFA francs (RM373,903). But the smugglers can earn over US$240 (RM1,018) a week, more than three times the country’s living wage. The trade has become increasingly worth the risks as cocoa prices have spiked. “God has been on our side this season,” said Fred, a smuggler in the border town of Danane, who asked to be identified by a pseudonym to avoid retribution.

Prices for cocoa on the global market have nearly tripled since 2023, reaching around US$13,000 per tonne in December, before falling back to around US$9,000. Adverse weather and disease outbreaks have exacerbated supply issues caused by decades of underinvestment in major producing countries, leading to severe shortages. But as prices soar, farmers in Ivory Coast, the largest exporter of the crop, have found it hard to cash in. The cocoa trade in the country is controlled by a government-run regulator, the Conseil du Café-Cacao (CCC), which sets prices. The current CCC price is about a third of the global market price, which has created a powerful incentive to smuggle crops into neighbouring countries that don’t have the same central pricing.

The surge in smuggling has made it harder for international buyers to source beans, as Ivorian suppliers struggle to fulfil their contracts. It has made traceability more difficult, a major problem for companies trying to address long-running issues of deforestation and child labour in their supply chains. For the Ivorian government, smuggling has cut revenues, undermining its national budget and its ability to invest in the long-term future of the cocoa industry.

“There is a huge loss of Ivorian harvest,” Arsène Dadié, director of domestic marketing at the CCC said, in an interview in Abidjan, Ivory Coast’s commercial hub.

Illicit Flows

The CCC sells cocoa crops months ahead of harvest, which helps them to set a guaranteed price for farmers at the start of the season. That meant that as prices rallied last year, regulators had already committed to sell most of their cocoa well below the global market price.

Farmers typically sell to brokers and middlemen who aggregate the crops and sell to major buyers, such as Barry Callebaut AG, Cargill Inc, Olam Group Ltd and Touton SA.

Ghana, the world’s second-largest producer, has a similar setup to Ivory Coast, with the Cocobod acting as a central buyer. Output in Ghana fell to its lowest in more than a decade last season. Smuggling exacerbated the supply shortfall.

In April, prices in Guinea, Togo and Liberia were more than double those the CCC was offering, creating an arbitrage that some farmers and middlemen couldn’t resist exploiting.

The scale of the smuggling can be estimated from the growing disparity between Guinea’s production and exports. Guinea hasn’t appreciably invested in increasing its domestic cocoa crop, but in the 2023-2024 growing season, shipments from the country rose 15% over the previous year, according to data provider Trade Data Monitor. That growth has continued. In the first three months of the current season, starting October, Guinea’s cocoa shipments were more than twice the previous year.

“You can assume that Guinea has been enjoying nice prices and increasing its production, so maybe a 10% increase would be a good accomplishment already but not enough to move from 25,000 to 95,000 tonnes,” said Fabrice Laurent, founder of cocoa research firm Forestero.

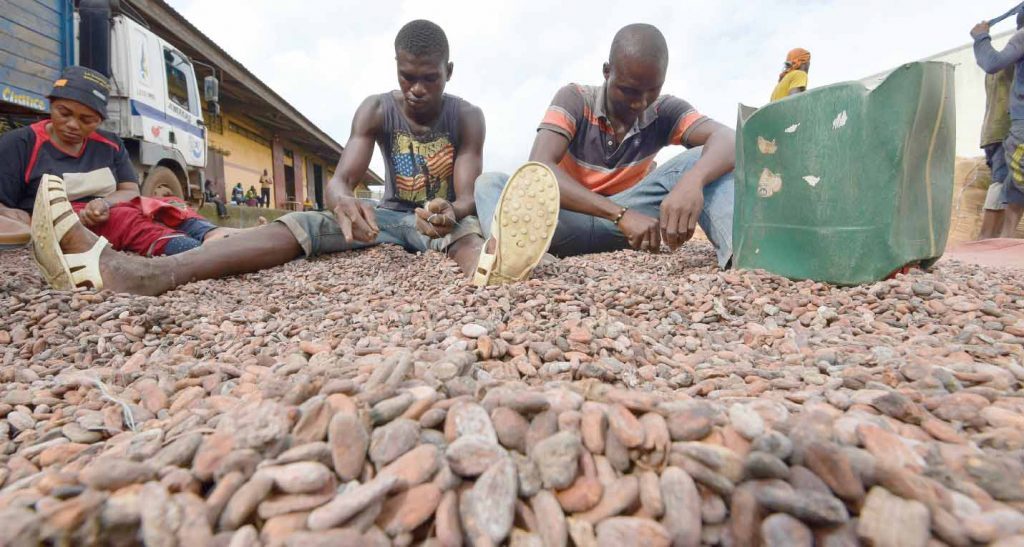

Fermented cocoa beans drying in the sun on a farm in Azaguie, Ivory Coast

The bulk of Guinea’s cocoa ends up in Europe, with the Netherlands accounting for about 70% of all Guinean exports between January and December, according to Trade Data Monitor data.

Over the 2023-2024 season, beans arriving for export at Ivorian ports dropped by 30%. Some of the drop is down to bad weather that battered crops, but Laurent estimates that around 100,000 tonnes was smuggled out of the country, mostly into Guinea, Togo and Liberia. That compares to the total harvest of about 1.7 million tonnes. With every smuggled tonne of beans, the country is losing out on export duties. The cocoa sector accounts for about 40% of Ivory Coast’s export revenue, making it a vital source of foreign exchange (forex).

The rise in illicit flows has left buying agents struggling to find enough cocoa to fulfil their contracts with international traders. Last year, exporters faced significant losses after both Ivory Coast and Ghana were unable to honour presold contracts. Frustrated traders in Abidjan, speaking on condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive information, said they were torn between breaking the law and overpaying to source supplies, or failing to meet their obligations. Several admitted that they are now paying a premium over farmgate prices to secure beans, in defiance of CCC rules against overpaying.

Cocoa traders typically hedge their physical purchases by selling futures contracts. Delayed cocoa shipments last season forced traders to buy back their short positions and initiate new ones at a time of rapid price inflation, with futures climbing from roughly US$3,000 to US$11,000 per tonne. One of the traders said that they lost £2,000 (RM11,515) on every tonne’s worth of defaulted contracts, as they were forced to roll over futures contracts at higher prices.

The rise in smuggling complicates chocolate makers’ efforts to improve traceability in their supply chains. Consumers are increasingly conscious of human rights and environmental risks in the cocoa business, which has put pressure on companies to invest in understanding where their beans are grown. At the moment, traceability is largely voluntary, but that will change for large companies in Europe when the European Deforestation Regulation, or EUDR, comes into effect on Dec 30. The law will require that traders provide documentation tracing supplies back to the farm level.

“People are bracing for EUDR and even though supply was tight, major traders were not willing to buy cocoa just from anyone,” Jonathan Parkman, head of agricultural sales at Marex Group, said. That makes smuggling a top concern for traders and buyers, he added.

Bloomberg met with traders in Abidjan and middlemen in the western towns of Danane and Duékoué, who spoke on condition of anonymity to avoid reprisals. They said that they felt that the government isn’t doing enough to crack down on smuggling, however, and that corrupt officials are aiding the illicit trade in beans across the border.

While smugglers like Fred move small cargoes of cocoa into Guinea, much of the trade happens in bulk, with organised, politically-connected networks moving trucks carrying upwards of 30 tonnes of cocoa at a time, according to smugglers, officials and traders. That’s an expensive exercise, as the smugglers need to have enough capital to buy the beans from farmers or brokers, pay for logistics and spare some money for bribes. Bribes range from US$8,000 to US$21,000 per truck, according to smugglers and traders who asked not be named so they could discuss sensitive information.

“It’s the influential business people who have mastered the art of smuggling these goods, also working with civil servants who are happy to get their cuts from it, so it’s a chain,” Ndubuisi Christian Ani, a Nigeria-based analyst at the Institute for Security Studies think tank, said.

A cocoa processing plant in Abidjan

Dadié, from the CCC, said that the government has stepped up its anti-smuggling efforts. “It’s a well-organised network but the CCC is working with the local anti-smuggling system to increase monitoring,” he said.

This season the military was deployed to the border, and the Ministry of Interior has set up regional anti-smuggling committees with the regulator. They are tasked with publicising and combating illegal cocoa sales, a CCC spokeswoman said. “As soon as the task-force was set up, we seized three trucks and saw that a certain number of administrative actors who did not subscribe to this vision were sanctioned,” Dadié said.

In a statement, Fidèle Sarassoro, head of Ivory Coast’s national security council, said that anti-smuggling operations set up in October last year had achieved “significant results,” including the seizure of more than 590 tonnes of cocoa, and the arrest of 34 people. In February, Ivorian customs seized a stock of 2,000 tonnes of cocoa, worth around US$19 million, which had been falsely declared as rubber.

The leakage of crops, on top of the other structural challenges to the industry, is leading to frustration throughout the supply chain. In Duékoué, a town 400km from Abidjan, Abdul Baudula, the head of a farmers’ cooperative that aggregates beans, said that the organisation failed to meet its collection targets last season, partly because farmers sold their crops to be smuggled.

“How do you convince a farmer to accept less money when another trader is offering more?” Baudula said. “We can’t control climate change, but smuggling should be something the government can address.” — Bloomberg

- This article first appeared in The Malaysian Reserve weekly print edition

RELATED ARTICLES

From bean to bar, Haiti’s cocoa wants international recognition

It’s chocolate factory or cocoa farm in Malaysian growth toss-up

Guan Chong to match world’s top cocoa grinders in 5 years

Higher plant utilisation keeps Guan Chong afloat

Cocoa, cocoa products export revenue at RM 3.6b as of June 2022

Systemic changes needed for sustainable cocoa production

The post High cocoa prices drive smuggling surge, alarming traders appeared first on The Malaysian Reserve.