Dozens of India’s big-ticket infrastructure projects have underperformed, echoing China’s problems of the past

by MIHIR MISHRA

WHEN Indian officials inaugurated a new airport in the small city of Hisar, the ambitions were grand. With planned capacity for a couple million passengers, the local government touted its benefits as an alternative to the much busier terminals serving nearby New Delhi.

But several years after the ribbon-cutting ceremony, Hisar’s airport is still barely functional. The arrival and departure halls are mostly empty, and stray dogs lounge on the runway. Though the airport hosts military jets and sporadic planes ferrying politicians, only a handful of subsidised commercial flights have lifted off from Hisar since 2021.

Underperforming Projects

“Nothing substantial has happened,” said Subham Nagpal, 43, who owns a shop in a nearby market.

The scene tracks across India. Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his deputies have rapidly shored up infrastructure in the world’s most populous nation, spending billions to expand highways and ports, and building dozens of new airports.

Yet India’s sometimes blinkered commitment to improving connectivity hasn’t always matched the ground realities of supply and demand. Dozens of big-ticket projects are underperforming, echoing China’s problems of the past, when Beijing pumped money into roads, luxury condos and airstrips in cities devoid of people or commerce.

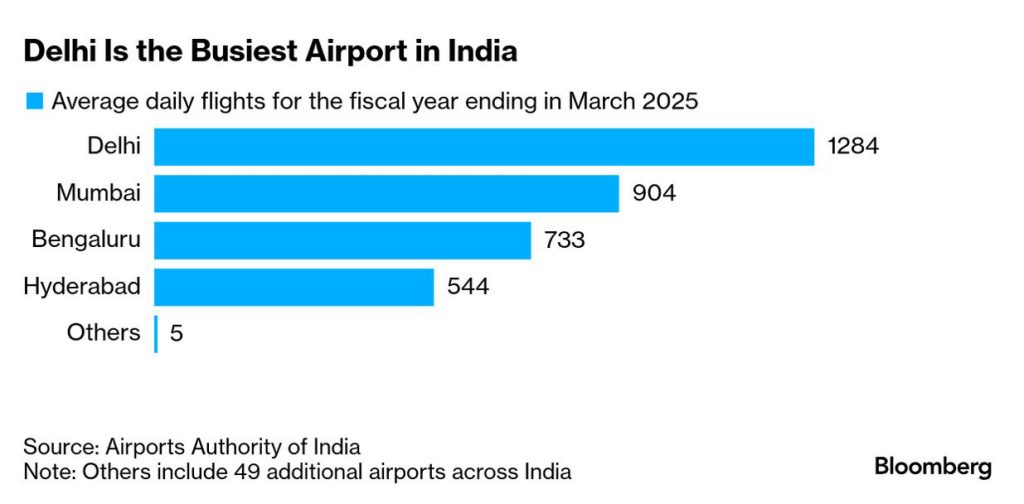

Of India’s 140 airports, a dozen terminals didn’t see a single passenger between December and March, effectively rendering them ghost airports, according to official aviation data. More than a third averaged less than five daily flights for most of last year, with some recording zero on certain days.

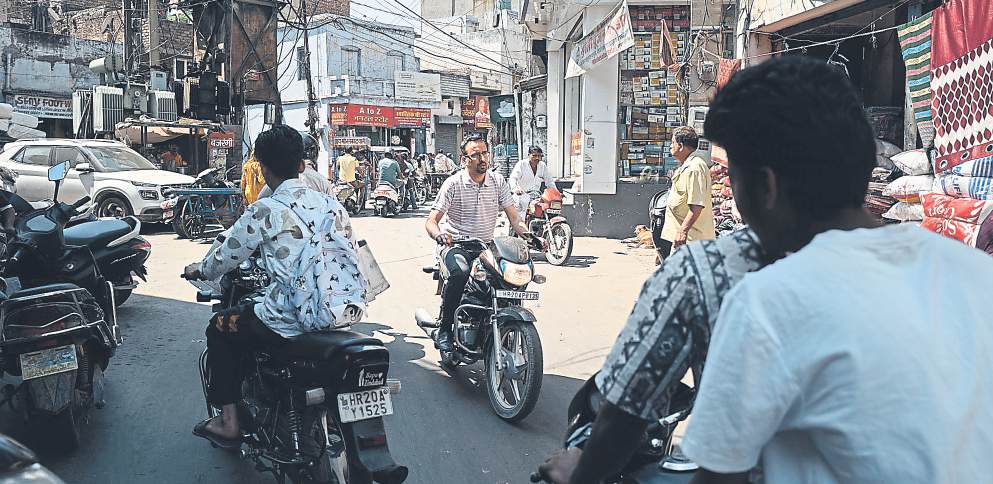

The town centre of Hisar, where residents are mostly happy just to have an airport, even if regular flights have yet to follow

Indian officials are now questioning whether too much was built too quickly — and if the nation’s growth story is starting to show signs of wear and tear. Parts of the economy have lately wobbled, most recently illustrated through a US$1.3 trillion (RM5.63 trillion) stock rout.

Though share prices have rebounded over the last few weeks, India’s GDP is expanding more slowly than in the past. Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs Group revised their forecasts downward to 6.1% for the current fiscal year. That’s far below growth of more than 9% in recent years.

Pork barrel politics is one backdrop for India’s infrastructure challenges. Elected leaders at the regional level are under pressure to fund flashy projects to impress voters, even if blueprints are poorly designed and average ticket prices are still too expensive for most of their constituents. The chief minister of Madhya Pradesh, one of the country’s poorest states, recently promised to build one airport for every 200km of land.

“Clearly, India is not planning its aviation infrastructure based on traffic and demand logic, but on election and political agendas,” said aviation consultancy firm Martin Consulting CEO Mark Martin.

“The way infrastructure is being created at places where no industrial or population catchment exists raises questions on whether someone is financially benefitting from these projects,” he added. “That’s the last thing India needs given the insane public debt and fiscal deficit.”

Workers installing a sign at Hisar Airport. Average ticket prices at regional airports are still too expensive for most constituents

A Wealthier Future

In the country’s megacities, many metros are struggling. Mumbai’s ridership is about 30% of its original target, and Bengaluru’s is 6%. Other than New Delhi and Kolkata, actual ridership in metros across India is less than 20% of desired levels. The government’s official auditor has in the past said some projects were constructed years — or even decades — before they were needed.

Though the road network has grown dramatically, at times legal disputes between private firms and India’s state builder have dragged down highway projects connecting crowded cities like Ahmedabad.

India’s empty airports are perhaps most emblematic of the nation’s construction woes. While air traffic numbers have never been higher in India, questions persist about whether tax dollars are being spent efficiently in places where passenger bottlenecks are most obvious, typically high-traffic metros like New Delhi and Mumbai.

“These airports are facing demand challenges and this will continue in the near term,” said aviation consultancy firm CAPA India CEO and director Kapil Kaul.

The state-run Airports Authority of India (AAI), which manages 100 facilities across the country, didn’t respond to requests for comment.

In public statements and on campaign trails, Indian officials have argued that the airports are necessary to prepare for a wealthier future, even if they’re underutilised in the present.

Since the pandemic, air traffic growth in India has outpaced practically every other major economy. Today, India has the third-largest domestic market for air travel behind the US and China. Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party want to double the number of airports by 2047 — the deadline India has set for becoming a developed nation.

Check-in counters at Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj International Airport in Mumbai, where there are passenger bottlenecks

During a regional election rally a few months ago, Modi landed at the Hisar airport and trumpeted the city as an example of India’s march to modernisation. In April, state-owned Alliance Air started sell- ing limited flights between Hisar and New Delhi, though it’s unclear how long they will last unless the government continues to subsidise them.

Local officials are also considering offering cheap parking for planes that want proximity to New Delhi, which is less than 200km away.

While Alliance Air starting some flights from Hisar is promising, the carrier’s past efforts haven’t always helped. The airline commenced flights to the Pondicherry airport from Bengaluru in 2014, but stopped services within six months, according to a local media report.

Ghost Towns

Globally, there’s precedent for India’s strategy of building first and utilising later. A decade ago, China was also criticised for “ineffective investment” in its so-called ghost cities. In response to rapid urbanisation, the government financed a building spree that yielded a number of bizarre white elephants: Vacant apartment buildings sinking into pits of mud; wide, empty highways; and extravagant architectural showpieces with no obvious function.

Yet some of China’s former ghost cities, such as in Pudong district, aren’t doing half-bad today, especially those that were built to absorb the overflow from megalopolises like Shanghai.

Whether India’s white elephants will become similarly viable remains a question mark. Logistics are more complicated to solve than in communist China. India’s messy, democratic system frequently leads to bureaucratic gridlock.

India’s ghost airports, for example, are often located in small cities with airstrips that only accommodate commuter-type aircraft, which is limited in the country. And compliance costs related to security and traffic management are currently fixed across the industry, meaning regional airports and busy international airports pay basically the same amount, despite having vastly different balance sheets.

“It is difficult to make any airport with smaller aircraft operations work financially,” said AAI former chairman VP Agrawal.

Chauhan’s yet-to-open new restaurant across from the airport. He plans to open it once traffic starts flowing through the terminals

Current officials with the AAI have privately complained about the rising number of loss-making facilities. In a report reviewed by Bloomberg News, the AAI raised the possibility that the government may need to offer “viability gap funding” to struggling airports for another 10 to 15 years. Smaller airports require at least eight to 10 commercial flights a day to recover their operating costs, according to an estimate in the AAI report. Half of AAI’s 140 airports host less than 10 flights a day, data analysed by Bloomberg News shows.

The government money is geared toward democratising travel for India’s 1.4 billion people, especially those living in hard-to-reach pockets of the hinterland. The extra cash falls under a programme with a name that translates to “let common people fly”. India has set a target of launching subsidised flights to 120 new destinations.

Road blocks on a deserted road to the airport. India’s narrow focus on connectivity often overlooks real supply and demand needs

More Business

But Agrawal, who now works as an aviation consultant, said these steps may not be enough to turn around India’s ghost airports. Until the government adjusts compliance costs to reflect the size and scale of an airport — like it is in the US, for example — “India will never be able to develop financially sustainable airports in smaller towns and cities,” he said.

In Hisar, home to several hundred thousand people, residents were mostly happy just to have an airport, even if few flights have yet to follow.

Prakash Chauhan, 40, who runs a cafeteria nearby, already has plans to open a bigger restaurant once traffic starts flowing through the terminals. “That will mean more business for us,” he said.

A monkey drinking water on the grounds of Hisar Airport. Only a handful of subsidised commercial flights have lifted off since 2021

At Hisar’s bustling Raj Guru Market, amid the “sari” and sweet shops, many said the new infrastructure isn’t simply about improving life in the city, but also a first step toward attracting outside investment. Some drew a parallel to the fortunes of Gurugram, a city of farmers near New Delhi that’s now one of India’s main business hubs and a magnet for multinationals.

Santosh Gundli, 40, who’s eager to take her first trip on an airplane, brushed aside concerns about breakneck construction in the country. These projects are ultimately about manifesting a more prosperous India, she said, and that’s a vision everybody in her circle is eager to believe in.

“The flights will be good for our future generations,” Gundli said. — Bloomberg

The post Empty new Indian airports echo China’s past infrastructure pains appeared first on The Malaysian Reserve.