The outspoken host of ‘The Smoking Tire’ videos and podcasts has become an unlikely advocate for urban transportation policy reforms that limit car use

by DAVID ZIPPER

MATT Farah wanted to tell me about his ride.

“This is a final-year car,” he said of his 2005 Acura NSX, a mid-engined supercar he was steering through Los Angeles (LA) traffic. “By the time they got to the very end, Acura wasn’t selling very many. There were only 248 NSXs built in 2005, and this is one of 30 they built in silver.”

Farah accelerated onto the freeway, and I felt the Acura’s power. Noticing my reflexive grip on the door, his round face broke into a grin. “We’re barely over the speed limit,” he said. “I like the NSX because it feels like you’re going 100 when you’re only going 80.”

Moments later, Farah yelped and pointed. We were passing some kind of vehicular Frankenstein — a classic pickup cab seemingly soldered onto the back of a race car. “Look at that thing!” he exclaimed, his eyes widening. “That is some California car-building stuff right there.” The driver smiled and waved when he noticed us gawking.

If you’ve never heard of Matt Farah, he’s one of the biggest automotive personalities of the digital era. An ebullient podcast host, content creator and car influencer, his media platform, The Smoking

Tire, counts more than a million YouTube subscribers; Farah has reviewed more than 2,000 vehicles there. According to its website, Farah “made his first YouTube video in 2006 and has done nothing but talk about cars ever since.”

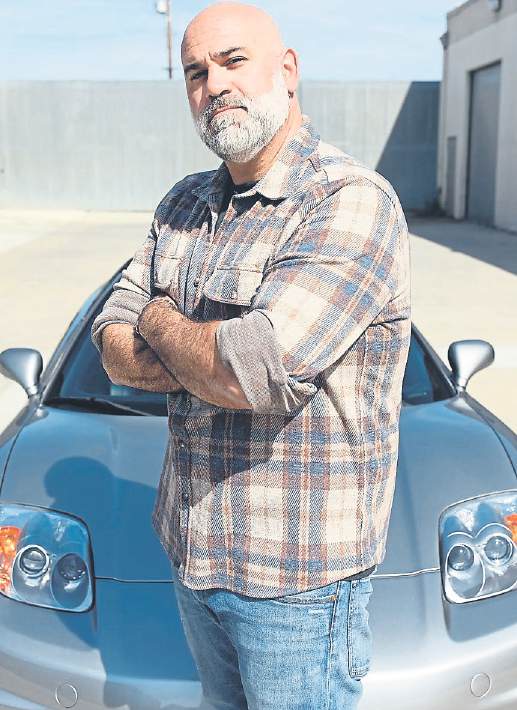

Farah poses with his 2005 Acura NSX

But Farah also speaks forcefully — and knowledgeably — about the costs of constructing our lives around motor vehicles.

“In this city, some of the most desirable places to live are the most walkable,” he told me over lunch that afternoon. “But you can’t build more places like that right now, because of parking minimums and stupid stuff like that.”

In addition to gushing over the latest Lamborghinis, Farah can hold forth on the benefits of multi-modal streets, the perils of car bloat, and the upsides of upzoning. He believes that it’s entirely possible to love cars while recognising that cities would be better if fewer people used them.

“LA is a place that doesn’t understand the difference between car dependence and car enthusiasm,” Farah said. “If I can just make that one point, I think that would do a lot of good.”

Like so many topics in today’s polarised world, popular views on transportation often reduce to a dichotomy: Cars are either good or bad. Among progressives who promote safer, cleaner and more affordable travel, the latter view dominates. On the other side, conservative voices, including those within the Trump administration, tend to frame the distinction on ideological lines, condemning traffic-fighting policies like Manhattan’s congestion pricing programme as an assault on personal freedom.

For advocates of better urban mobility, allies like Farah are urgently needed. He’s mastered social media channels that conservatives have come to dominate, and he reaches an audience that isn’t reflexively supportive of bike lanes and road diets. At the same time, gearheads owe it to themselves to consider the environmental and social costs that their preferred mode exacts on cities, a tension that Farah doesn’t shy away from.

When Farah started a storage business for collectible cars, he learned about LA’s parking regulations and discovered the importance of urban policymaking

I first met Farah in 2022, through Alex Roy, an automotive writer and endurance rally driver who once set a record for the Cannonball Run, the infamous extralegal New York-to-LA race. “You guys will either love each other or hate each other,” Roy said as he introduced us at a transportation convening in Germany.

A year later, Farah invited me to be a guest on his podcast. We clashed over my support for speed-limiting technology, but still found plenty of common ground. “No one likes traffic,” Farah said during the episode, “but urbanists and car enthusiasts hate traffic even more than regular people do.”

A few months ago, I flew to California to spend some time with Farah driving, walking and biking around LA. My goal: Determine whether the phrase “urbanist car bro” is really a contradiction in terms, or an opportunity to side-step today’s toxic transportation discourse and build a broader coalition for change.

Farah texted me directions to the spacious one-story home in West LA he shares with his wife and four cats. “When you get into my neighbourhood, look for all the anti-upzoning signs,” he said. As my Lyft pulled up, Farah greeted me with a fist bump. Burly and bald at 43, with a salt-and-pepper beard, he wore a custom baseball cap adorned with a no-speed-limit sign from the German autobahn. The backs of his calves have matching tattoos: “Clutch” and “Gas” (in the appropriate order).

Farah’s home is full of automotive décor — a grown-up version of a car-crazy kid’s 1990s bedroom. A hallway wall showcases a photo of a 1988 Lamborghini Countach 5000QV, one of the seven cars he owns, and his garage features 3D printed maps of famous racetracks like Road America in Wisconsin and Germany’s Nürburgring. (Two bathrooms have decor devoted to the Oscar Mayer Weinermobile and the movie Demolition Man respectively.) But on a bookshelf in the office, you can also find a row of wonky titles familiar to many trans- portation professionals, like Spencer Headworth’s Rules of the Road, Peter Norton’s Fighting Traffic and Sarah Seo’s Policing the Open Road.

After college, Farah opened a car detailing shop in Westchester County, NY

“Matt is like a centrist Joe Rogan who actually reads the books,” said Roy, who has known Farah for two decades. “And he has read all the books.”

Farah grew up in Westchester County, outside of New York City, where he drove a Ford Mustang to high school and opened a detailing shop after college. He and a few regular customers would go on drives together on winding roads in New York and Connecticut. “I started filming them, and that’s how I began my YouTube career,” he told me at a sandwich place near his house. “Very quickly I realised I liked making videos a lot more than I liked detailing cars.”

Our table was outdoors facing the street. Every few minutes, Farah would spring up like a jack-in-the-box- box, gesturing toward a passing vehicle — “That was a Porsche 911!” — before sitting back down.

In 2009, Farah moved to LA, a hotbed of American car culture and automotive media. By the mid-2010s, The Smoking Tire had become a go-to resource for those wanting to learn about the latest models or just live vicariously through Farah as he filmed himself behind the wheel of rare gems like an Aston Martin V12 Vantage or a McLaren 750S.

In 2016, Farah decided to capitalise on his automotive know-how

by launching a storage business for collectible cars. He acquired land in Playa Vista to build a garage, but he soon ran into a regulatory roadblock: A city law demanded dozens of basement parking spots. “I had a mandatory parking minimum, even though what I was building was itself a parking lot,” Farah said. “Having to build a parking lot for your parking lot is dumb as rocks.”

That experience radicalised Farah against parking minimums — a bugaboo of urbanist policy — and led to him to discover the work of Donald Shoup, the late UCLA professor whose book The High Cost of Free Parking is a bible for trans- portation policy reformers.

Farah’s The Smoking Tire YouTube channel has more than 1m subscribers

Frustration with zoning wasn’t the only reason Farah’s perspectives shifted around that time. Although he hadn’t had particularly strong political views, “Trump getting elected was a real shock,” Farah said. “It led me to start reading people like [Princeton historian] Kevin Kruse and learning about transportation policy like busing for school integration. I started thinking about racial hierarchies and redlining, and — what’s his name? That guy in New York. Robert Moses.”

Autonomous vehicle technology was grabbing headlines at that time, too, with boosters hailing it as a safety breakthrough. Farah found the hype overblown.

“People were saying, ‘We need this because it’s safer,’ and I was like, hang on a minute. This is pretty much untested, unregulated software. We haven’t even tried any of the thing that we know works yet — traffic calming and painted bike lanes, for instance. Because I’ve been to other places that do use

those things, like Amsterdam and Copenhagen. The idea that we can’t use those things here is stupid.”

When he’s not ripping awesome burnouts on camera, Farah often discusses topics that car enthusiasts may not consider. Over the last few years, he expanded The Smoking Tire’s guest list beyond drivers, carmakers and collectors to include transportation academics and urbanist writers. Recent episodes have featured Johns Hopkins road safety researcher Shima Hamidi, Paved Paradise author Henry Grabar, and former Curbed writer Alissa Walker.

“Matt has a way of bringing you along with him for the journey,” said Walker, who talked with Farah about the expansion of the Los Angeles Metro. “I think that’s where he excels. He’s going to bring you through the issue in a way that you’ll understand.”

Not infrequently, Farah’s commentary aligns with critiques from safety advocates. He once pressed Ford CEO Jim Farley to explain why the company eliminated its North American lineup of sedans in favour of trucks and SUVs, and his video review of the Tesla Cybertruck mocked its potentially dangerous design. (“You can make a nice salad with this thing,” he observed, peeling a cucumber on the body’s sharp edge.)

Some of his musings might sound more at home on a very different podcast. “A reduction in the number of cars will solve so many problems: The problem of insufficient space, the problem of emissions, the problem of wear and tear on our infrastructure,” he told me.

Farah knows that many of his fans don’t share his reformist views. “You should see what happens when I verbalise that I feel guilty taking up so much space in [a big car],” he said. “You should read the comments on posts like that. The backlash is crazy.” He seems unfazed; his handle on several social media accounts is now Matt “Stick to Cars” Farah.

“He has strong moral authority,” Roy said. “Without question, the growth of his audience is different because he takes these stands. I respect him for it.”

Farah is not the only voice in car culture that skews progressive on urban issues. In the UK, former Top Gear host James May is an outspoken London cycling advocate. San Diego automotive influencer (and frequent Smoking Tire guest) Doug DeMuro, who has almost five million YouTube followers, describes himself as “a huge supporter of transit and of density, from a level that is almost sort of extremist.” (One of his California license plates reads “YIMBY.”)

DeMuro, who also founded the auction site Cars & Bids, believes that abundant housing and transit would allow more people to appre- ciate automobiles the way he does: “If we took driving back into an activity that was something you did occasionally, maybe on the week- end in a fun car, I think a lot more people would be into it.”

Farah agrees. “American policies have been subsidising car owners at the expense of non-car owners for a long time” he told me. “If I have to give up something in order to balance that scale, that’s OK. The ultimate result might be less congestion, which makes my driving experience better. I don’t collect sports cars to hurl them into 405 traffic.”

I asked Farah if there is a tension between his belief in his support for less driving and his ownership of seven cars and two car storage facilities, including a second one he opened in South Bay in 2023.

“No, because my cars spend 99.9% of their lives parked,” he said. “I may be taking up space, but I’m taking up space on my own private property — vertically.”

Despite being a car enthusiast, Farah believes that a reduction in the number of cars will solve a lot of problems

After lunch, Farah drove us to Abbot Kinney Boulevard, a bustling corridor in LA’s Venice neighbourhood, and launched into a tutorial in multimodal road design.

“I’d close one of these three lanes,” he said as we strolled along the street. “I’d have a very slow thoroughfare in both directions, with a proper dedicated bike lane. Venice is the perfect place to bike: It’s flat, and the weather is always good. If you could connect to the bike path from Main Street to Venice Boulevard, you’d have a triangle. Anything inside it would be incredibly easy to reach by bicycle.”

Later, we rented bikes from LA’s Metro Bike Share so Farah could give me a tour. He lived in Venice until a few years ago, often using a Giant commuter bike to get around. “I customised it a lot, with different seat, different bars and a different gearset,” he said as we rode along the beach, a breeze blowing from the Pacific. “After a while, I was like, ‘yeah, let me just buy a nicer bike’ — which is also exactly how it goes with cars.”

We turned inland to check out the canals that give Venice its name. “I should bring my wife here and go biking,” he said. “If we move again, our next house will have a little less property and be in a more walkable neighbourhood. That’s something we didn’t know how much we valued until we didn’t have it anymore.”

Walker is also a LA resident — she recently launched a newsletter on LA’s 2028 Olympic Games preparations — and she often comments on local issues. She sees Farah as an ally. “People who live in those wealthier neighbourhoods in the Westside need to get more involved with building housing and more transit,” she said. “For him to acknowledge that’s what we have to do — it’s good to have that person on our side.”

But she’s not sure that activists supporting zoning reform or multi-modal transportation understand how gearheads like Farah can advance their cause. “Sometimes advocates position themselves as the enemy of the driver, so people just think that they’re anti-car,” she told me.

Farah said that terms like the “war on cars,” can be counterproductive. “Car enthusiasts hear talking points like that and think ‘They’re going to take your cars away.’ Of course nobody wants to do that.”

As we cycled through his city, I asked Farah if he had ever testified at a local public hearing in support of bike lanes or upzoning. He seemed surprised by the question.

“No,” he said after a pause. “Nobody ever asked me.” — Bloomberg

- This article first appeared in The Malaysian Reserve weekly print edition

The post Why car YouTuber Matt Farah is fighting for walkable cities appeared first on The Malaysian Reserve.