Not since the 1990s have luxury brands gone to such lengths to turn around their fortunes

by DANA THOMAS

NEW York socialite Nan Kempner had been a Dior couture client for some 50 years when the iconic French fashion house replaced its lead designer with a splashy new talent in 1997.

That year, as she watched daring new looks parade by, she commented wryly that her stately fellow audience members French first lady Bernadette Chirac and former first lady Claude Pompidou “looked like they had been hit in the face with a cold dead fish.”

That designer was John Galliano and that year became known in the luxury fashion industry as the Big Bang. In the 1990s, business tycoons, such as LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton SE’s Bernard Arnault, saw the immense financial potential of luxury in the age of globalisation and started snapping up old-fashioned and leather-goods companies.

They then hired a cohort of young designers, with a mandate to reinvigorate — and rejuvenate — the creative side. The first was Tom Ford at Gucci in 1995. For his premiere he presented sexy velvet hipsters and jewel-tone silk blouses.

In the two years that followed, Gucci sales increased 90%. Then, in 1997, almost a dozen designers had made their debut at stalwart houses, including Galliano at Dior, Alexander McQueen at Givenchy, Michael Kors at Celine, Narciso Rodriguez at Loewe, Marc Jacobs at Louis Vuitton (all LVMH companies), Stella McCartney at Chloé, Alber Elbaz at Guy Laroche, Nicolas Ghesquière at Balenciaga and Martin Margiela at Hermès.

The impact was seismic. With their theatrical runway shows and radical offerings, these young designers — rechristened “creative directors” — transformed how fashion was marketed and sold worldwide.

Almost 30 years later the luxury fashion business is going through a similar creative renaissance, or disorienting upheaval, depending on whom you ask.

More than 10 designers, including Jonathan Anderson at Christian Dior, Demna at Gucci, Pierpaolo Piccioli at Balenciaga and Matthieu Blazy at Chanel, showed their first collections for their new houses during the Spring-Summer 2026 women’s wear shows in Milan and Paris this fall.

“So many in one season — that has never happened before,” said Robert Burke, an American luxury retail consultant and former fashion director for Bergdorf Goodman.

Several more, notably Sarah Burton at Givenchy, Haider Ackermann at Tom Ford and Peter Copping at Lanvin, presented their sophomore collections. Some houses also introduced new young brand ambassadors, such as Gen Z actresses Mikey Madison, at Dior and Ayo Edebiri, at Chanel.

Modeling Dior’s ready-to-wear spring-summer 2026 collection, Jonathan Anderson’s 1st for the French house, which showed in Paris in October

The message was clear: Fashion is entering a new phase — generational, creatively and (the C-suite executives and investors hope) financially.

And it’s not a minute too soon. Luxury has been on a whiplash-inducing ride. After Covid-19 lockdown restrictions were lifted, luxury sales boomed — on reopening day in 2020, Hermès’ flagship in Guangzhou, China, rang up an astounding US$2.7 million (RM11.4 million), the highest single-day tally ever for a boutique in the country.

Then so-called greedflation set in, with brands such as Hermès and Chanel hiking retail prices exponentially (HSBC Holdings plc reported the average price of personal luxury goods in Europe has risen more than 50% since 2019) on the assumption that there was virtually no ceiling on what people would pay for coveted brand items.

But interest stagnated and sales stalled. Chinese consumers, who account for about a third of luxury fashion purchases, soured on the sector. Bain & Co reported that revenue in mainland China declined 18% to 20% in 2024, in part because of “low consumer confidence.”

Middle-market shoppers in the West, hit by inflation and job loss, turned to lower-priced “accessible luxury” brands, such as the French leather-goods startup Polène.

Not even high-net-worth individuals — the 1% who traditionally account for 30% of luxury purchases — could spend enough to make up the difference.

Overall, luxury fashion sales declined 2% worldwide in 2024, according to Bain & Co Chanel’s operating profits last year plummeted 30%. This year is better, but not much. In the first six months, sales for LVMH’s fashion and leather-goods division, which makes up roughly half of the luxury group’s total revenue, fell 8%; on Oct 14 the group reported an additional 2% loss for the division, to €8.5 billion (RM75.7 million).

Bernstein, a global equity research and brokerage firm, predicts Dior will suffer a 10% decline for 2025. “After Covid-19, luxury consumers felt satiated for a while. But now you need to give them something new to get them excited and to part with their money again,” said Luca Solca, a luxury business analyst at Bernstein. “That’s why you need innovation.”

Hence the designer shake-up and flurry of new creative directions. Some of the propositions were instant hits: The Chanel, Dior, Balenciaga and Loewe shows all received standing ovations. Anderson’s first Dior collections drew the hoped-for admiration from younger fans, Burke said.

Others weren’t as well received. More than one critic described Versace designer Dario Vitale’s parade of ill-fitting streetwear in sherbet hues as overpriced Benetton.

New Jean Paul Gaultier designer Duran Lantink made such a creative and graceless, left turn for the venerable French brand that Gaultier fans on social media called for his immediate ouster.

Nevertheless the designers did exactly what they were mandated to do: Make noise. Launchmetrics, a global data and analytics company, reported that 48 hours after Paris Fashion Week had wrapped up, it had generated US$1.1 billion in media impact value, almost the same as this year’s Cannes Film Festival and “cemented Paris Fashion Week’s evolution from a trade event into a key cultural moment of the year.”

That may be. “But what do these designers mean for brand perception?” Launchmetrics’ chief marketing officer Alison Bringé, asks pointedly. “And will they be able to convert it into sales?” Company executives certainly hope so.

Some wonder if the musical-chairs-like designer changes at fashion houses have a secondary purpose: To kill off the costly “star” designer role created by Galliano, McQueen, Ford and their brethren (like the current crop of designers, that generation was almost all men).

Chanel’s spring-summer 2026 women’s wear show, designed by Blazy

This, the thinking goes, would make the brand names stronger and let talent know they’re simply guns for hire. Indeed, LVMH last month announced it had moved former Dior creative director Maria Grazia Chiuri to the French couture house’s sister ready-to-wear brand, Fendi, in Rome — an assignment not regarded by fashion followers as a promotion. (Galliano, who worked for Maison Margiela for 10 years until last summer, was rumoured to be up for many of these posts, including a return to Dior, but is now currently jobless.)

If such managerial machinations are real, they seem to be working. “The consumer loves the label, rather than the designers,” Burke said.

But even that love can be fleeting. “Today fashion and luxury consumers aren’t very loyal at all,” Solca said. “They buy whatever is exciting. If you are a very important client” — those high-net-worth individuals who patronise luxury brands — “you get special treatment and that does create loyalty to a point. But the bulk of consumers buy from a large number of brands. They want to be surprised, they want a story to post on Instagram and WeChat. That’s how it works.”

“What is most important is newness, irrespective of designer changes,” said Rickie De Sole, VP and fashion director for the US department-store chain Nordstrom. “Where the item comes from is not the point.

It’s about what makes them feel stylish. Good product will always triumph.”

That’s especially true in Asia, luxury’s largest market, with 40% of all sales. On Little Red Book, a Chinese social media and e-commerce hybrid platform that specialises in lifestyle and has more than 300 million users, “there is a luxury hierarchy: Hermès is top, then Chanel, then Dior, then Vuitton,” said Jasmin Zhu, a luxury brand consultant in Hong Kong. “And followers are deeply rooted in their brands.”

After the shows this fall, the consumer perception of those brands shifted markedly: “Chanel is cooler and Dior is becoming more intelligent,” Zhu said.

“Dior will sell a lot of leather goods accessories in China. Across the luxury market, handbags will likely drive the business.”

Look no further than Anderson’s whimsical new take on Dior’s 1990s “it” bag, the Lady Dior, named for that era’s top style icon — and Galliano’s first Dior client — Princess Diana.

After the royal was photographed carrying the boxy handbag in 1995 (a gift, as it happens, from first lady Chirac), the company sold 100,000 at US$1,000 apiece, helping raise Dior’s 1996 annual revenue by 20%.

With ’90s nostalgia dominating today’s fashion and culture, a run on Anderson’s Lady Dior — decorated with cutesy bows and miniature daisies and priced from US$3,900 to US$10,000 — just might be enough to pull the brand out of its financial doldrums. Big Bang indeed. — Bloomberg

- This article first appeared in The Malaysian Reserve weekly print edition

The post Can fashion’s changing of the guard revive an ailing industry? appeared first on The Malaysian Reserve.

WHATEVER happened to the saviour of the Amazon?

WHATEVER happened to the saviour of the Amazon?

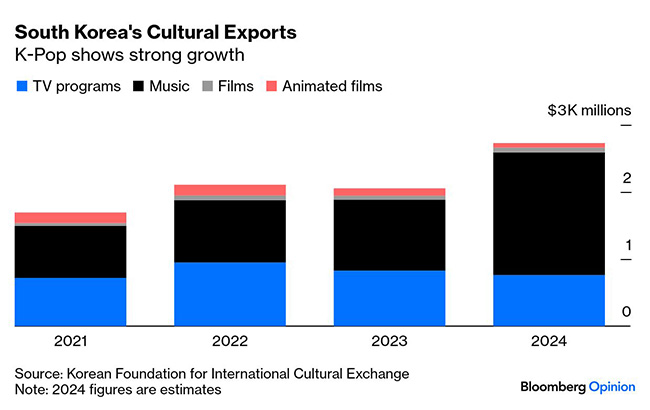

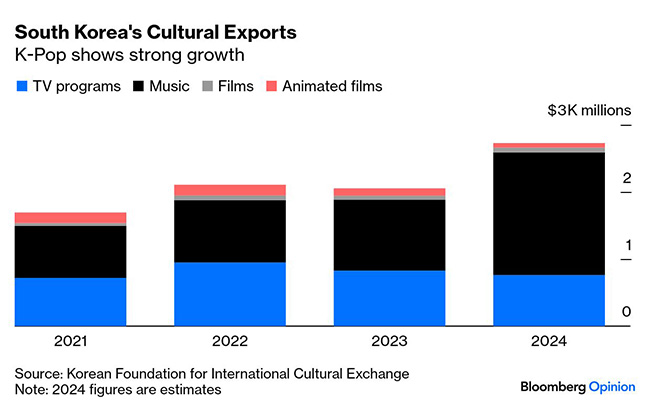

ANYONE with children endlessly rewatching KPop Demon Hunters might assume that South Korean content has already taken over the world. In fact, K-pop has enormous room to grow in a global music industry expected to be worth just under US$200 billion (RM838.2 billion) in 10 years. As it does, it should shake off any concerns about abandoning its roots. Like hip hop, there’s no reason why the genre can’t have a similarly inclusive trajectory while remaining true to its core.

ANYONE with children endlessly rewatching KPop Demon Hunters might assume that South Korean content has already taken over the world. In fact, K-pop has enormous room to grow in a global music industry expected to be worth just under US$200 billion (RM838.2 billion) in 10 years. As it does, it should shake off any concerns about abandoning its roots. Like hip hop, there’s no reason why the genre can’t have a similarly inclusive trajectory while remaining true to its core.