IF THERE’S one thing every American agrees on, it’s that politics has become vicious. There are plenty of explanations for why that is, from gerrymandering to the partisan sorting that has made both parties increasingly ideologically homogenous. One I’d add — but which often gets overlooked — is the slowdown in US technological progress outside of computing.

IF THERE’S one thing every American agrees on, it’s that politics has become vicious. There are plenty of explanations for why that is, from gerrymandering to the partisan sorting that has made both parties increasingly ideologically homogenous. One I’d add — but which often gets overlooked — is the slowdown in US technological progress outside of computing.

Technology is the most important driver of economic growth, and its rapid progress allows political disputes to centre on how best to distribute gains. That’s easy. What’s hard is when technology stagnates, growth slows and politics become zero-sum. The last few years have seen the promise of new technologies that could help us escape that trap — but the US President Donald Trump’s administration is throwing that opportunity away.

The idea that technological progress has slowed might seem counterintuitive when you consider the smartphone you prob- ably have in your hand right now. But George Mason University economist Tyler Cowen has mustered convincing evidence that that’s exactly what’s happening in nearly every field other than computing.

For example, the Wright Brothers made their first flight in 1903; both the Boeing 747 and the Concorde appeared less than 70 years later. If you had shown either jet to the Wrights, they would have thought they were hallucinating. Fast forward another half century and the differences between the 747 and a modern passenger plane are subtle, while no civilian aircraft approaches the Concorde’s speed.

The problem stretches far beyond aviation. The most basic measure of social wellbeing is life expectancy. Advances in technology, like vaccines and antibiotics, constantly increased our life spans during the 20th century. Yet American life expectancy peaked more than a decade ago.

Why is innovation in such a slump? Government is certainly part of the problem. Across many areas (particularly housing), bad policy is crippling growth, as shown by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson in “Abundance” and Marc Dunkelman in “Why Nothing Works”.

But there’s more to it. Science has, in Cowen’s words, plucked the “low-hanging fruit”. You can only invent penicillin or jet engines once. In drug development, progress has become so difficult that it’s governed by “Eroom’s Law” (Moore’s Law spelled backwards), which posits that the cost of bringing a new treatment to market doubles every nine years.

Similarly, since the 1970s, innovation has shifted away from material technologies and toward digital ones which are far less constrained by energy requirements and physical limits. Largely unchecked by antitrust laws, dominant technology companies like Alphabet Inc and Meta Platforms Inc have been able to form durable monopolies and capture the gains from these digital innovations, securing multi-decade positions atop a sector that was once characterised by constant ferment.

Technological advances can make everyone better off. If you’re reading this, you have more access to information and medical care than the wealthiest and most powerful people on Earth did when your grandparents were born. These gains make reform easier by creating a surplus, which can be used to compensate interest groups hurt by the changes.

When kerosene replaced whale oil for light, it devastated the whaling industry. But the benefits were so large that everyone, even (eventually) the communities that used to be supported by whaling, ended up better off. When that surplus goes away, people end up fighting much harder to avoid losses than they do to secure gains, making it difficult or even impossible to fix broken systems.

Healthcare reform, for example, has stalled at least in part because any change to the system would hurt someone. If healthcare technologies were still leaping ahead as quickly as they were when antibiotics first rolled out, improvements in quality and efficiency would create the slack to compensate those hurt by the reforms.

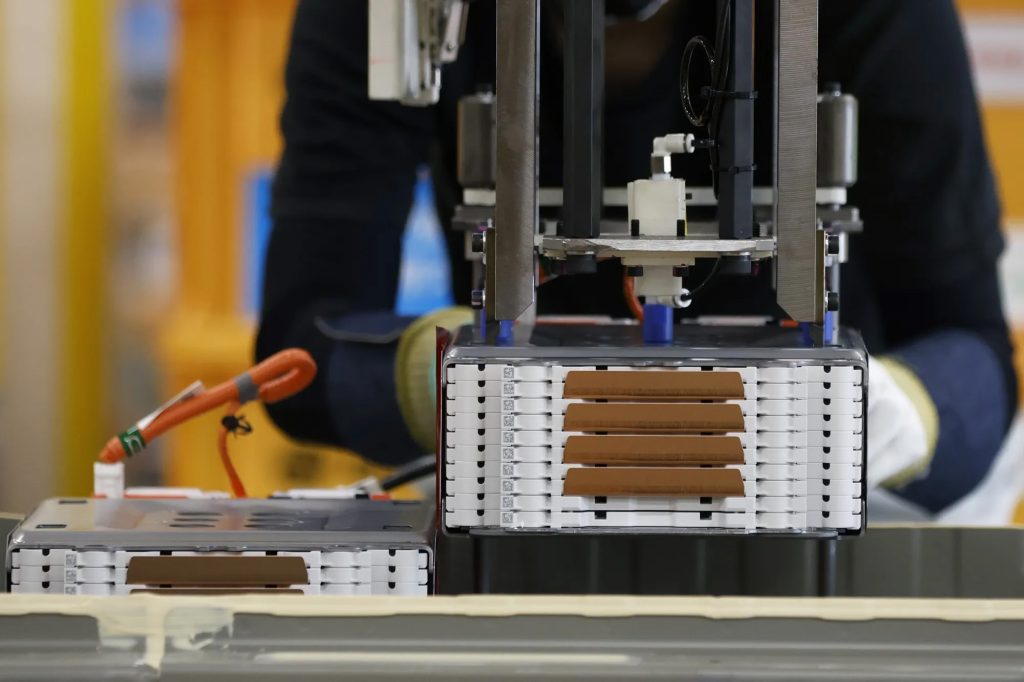

Recently, however, science and technology have offered the promise of revolution once again. On the energy front, the cost of utility-scale solar cells declined by 88% from 2009 to 2024. Similarly, the price of lithium-ion batteries declined by 97% from 1991 to 2021. This makes new renewable energy (RE) cheaper than new fossil fuels — and prices will continue declining.

Further in the future, breakthroughs in nuclear fusion pioneered by companies like Commonwealth Fusion Systems (a Massachusetts Institute of Technology [MIT] spinout) might offer energy abundance of the sort once imagined by 1950s science fiction.

There are other examples throughout the sciences. Merck & Co’s Keytruda and other immuno-therapy drugs have transformed the way we treat cancer. Space Exploration Technologies Corp (SpaceX) has cut the cost to put a satellite in orbit by a factor of 10. And artificial intelligence (AI) may supercharge our ability to innovate, ranging from biological and drug-discovery research to improvements in materials science that may drive advances in the field, including superconductors and quantum computing.

All these potential miracles, however, are being discarded. The administration’s new budget proposes a 55% cut to the National Science Foundation (the government’s primary arm for research outside medicine) and a 40% cut to the National Institutes of Health (America, and the world’s, foremost medical research institution).

These build on massive cuts to universities (most prominently Harvard, where I taught for many years, but others as well) where much of America’s most important research happens. Even the flow of scientific talent into the US — long one of the nation’s greatest advantages — is reversing, with top AI minds no longer coming here and the European Union (EU) allocating almost US$600 million (RM2.62 billion) to lure away top American researchers.

Science and technology can do amazing things. If we let them, they might even help fix our broken politics. The recent wholesale assault on science isn’t just a threat to the American economy or health. It’s a threat to the functioning of democracy, and perhaps our best shot at making it work better. — Bloomberg

- This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

- This article first appeared in The Malaysian Reserve weekly print edition

The post Slowing innovation is ruining American politics appeared first on The Malaysian Reserve.